Handoffs suck. They’re the worst part of building products. But many organizations seem designed to maximize the number of handoffs on a project.

Handoffs suck. They’re the worst part of building products. But many organizations seem designed to maximize the number of handoffs on a project.

Some teams are experimenting with new hybrid roles, like Product Engineer and Design Engineer, that can reduce handoffs and improve the quality of cross-functional decisions.

Let’s discuss how we can change the way we think about our work in order to:

- Replace handoffs with working together

- Design hybrid roles that eliminate handoffs

- Ship better and more holistic products

Administrivia

Welcome to the first entry of my summer-2024-only newsletter: :galaxy-brain: product engineering.

- Be sure to subscribe to find out about future posts.

- This newsletter is sponsored by my Funemployment Summer of 2024. I’m taking three months off to work on a few open-source projects and travel with my family over the summer. And then I hope to be employed again in the fall. Which means…

- I’m starting to look for a job. I’m an experienced product engineer and EM, with experience at Stripe, Vistaprint, and a number of startups. I’m looking for a remote-friendly team that’s doing high-quality web product work. I have deep experience with WYSIWYG UIs and payments. Check out my LinkedIn and website for more info. Please get in touch if you might have a good fit.

Handoffs

Ok, so back to our topic: what is a handoff and why are they so bad?

Imagine we’re building a generic web app. We need to pick a product direction, market it to users, design the UI, and write the code.

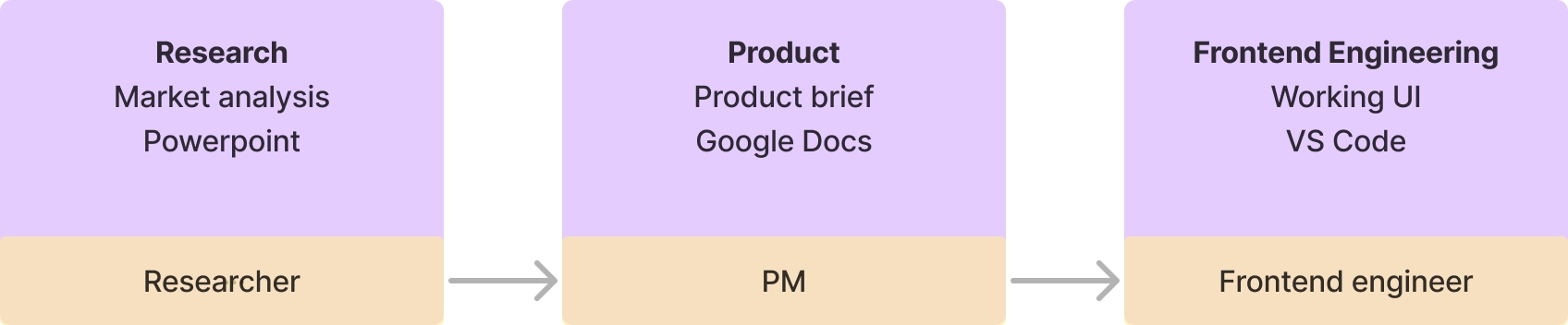

The most straightforward way to make this happen is to define roles in terms of the tool they use and the artifact they produce. We hire:

- a PM to write a strategy in Notion and some user stories in Linear

- a designer to make designs in Figma

- some engineers to write code in vim

So we often end up not really acting like a team, and we have handoffs:

- At a design review, the designer brings some mostly-finished designs and hands them off to the PM to turn into user stories

- At grooming or sprint planning, the PM brings some already-decided user stories and talks about them with the engineers

An aside: at this point, someone will object that they follow Agile or Lean UX, so they don’t have big handoffs between phases of a project. In my exprience, these processes are mostly about how projects are structured in time and how fast the feedback loops run. But that’s a different question from handoffs. Even if we don’t make a big plan up front, if designers are sitting in Figma and product managers in Google Docs, and just having meetings in between to catch up, that’s a handoff. It’s small and frequent, which is better, but nevertheless a handoff. (In contrast, some Agile and Lean teams do fully work as teams without handoffs. When they do, it’s usually because they have people filling the hybrid roles described below.)

Handoffs come from roles

Handoffs happen because we have someone working in one tool to make one artifact, and then we have to communicate that to a different person working in a different tool to make a different artifact.

Handoffs are painful because we take all of the complex thinking that happened in one area, reduce it to just a static artifact like a finished design or user story, and then ask people to act based on that artifact without seeing the thinking behind it. This produces a series of antipatterns:

- Local optimization: Each role makes decisions that are optimal for its own needs, without being concerned about the tradeoffs implied for other roles. (Sales sells something we can’t prioritize, design draws something we don’t have time to build, engineering sets a technical design that forces the UI to be slow, etc.)

- Missed opportunities: Each role is expected to present a single artifact, so if they have multiple, equivalent options, they have to pick among them arbitrarily. One they didn’t present might be optimal at other layers.

- Missing context: If a previous decision turns out to be unworkable, we can’t adapt quickly. We might have to go back through several layers and roles to understand whether the decision can be changed and think through all the downstream consequences of changing it.

While there are extreme forms of these behaviors that involve deliberate selfishness, more frequently they are well-intentioned misunderstandings that arise from working in different problem domains and not being able to predict how work in one area will translate into another.

When these handoffs become painful enough for a larger organization, we can redefine roles in order to improve or reduce handoffs.

Combining roles

When the pain points of one handoff are strong enough, it becomes tempting to simply combine multiple buckets of work and hire a unicorn who can do both well by themselves. In the past ten years, we’ve seen two common examples of this:

-

Fullstack engineering: as UIs get more complicated and add stronger demands on the backend, it becomes more painful to separate the work of deciding what APIs we need, designing them, building them, and then calling them from the UI. So it is convenient to simply combine the two concerns. We combine them at the people level by hiring fullstack engineers who can build the APIs they need to build a UI. And we combine them at the technical level: by consolidating onto a tech stack like JavaScript that we can use in both domains, or by promoting the contract into its own generic system, like GraphQL, so that the backend and frontend systems don’t have to do custom design work for the others’ needs.

-

DevOps: as backend systems scale and change at higher rates and our ops choices also change faster and grow more nuanced, it becomes difficult for one person to write the code and someone else to operate it at scale. So it becomes convenient to make the same people responsible for both.

These combined roles are useful in some contexts. If you can find someone who truly can do both sides well enough, that’s great. If you can make a team smaller so that they can go faster with more focus, that’s great.

But combining roles can also be a mistake:

- We might need more interview sessions and it will be harder to find people who do well in every area.

- Our culture might systematically undervalue one of the roles, and therefore never get better at it. Imagine we’re mostly backend-centric engineers, so we value and interview for that. Then we start calling ourselves fullstack. Instead of hiring someone with a very different skillset who can actually make us better at UIs, we might just stay mediocre at them forever. (This also happens in DevOps for cultures that don’t really understand ops.)

- When we try to combine neighboring roles, we can run into even more difficult combinations: if our org goes in for both fullstack and devops, will we be able to hire engineers who can do frontend, backend, and systems all at once?

Roles that are half a seat over

An alternative is to move roles “half a seat over”, so that they are aligned not to one artifact, but instead to translating between two ways of thinking.

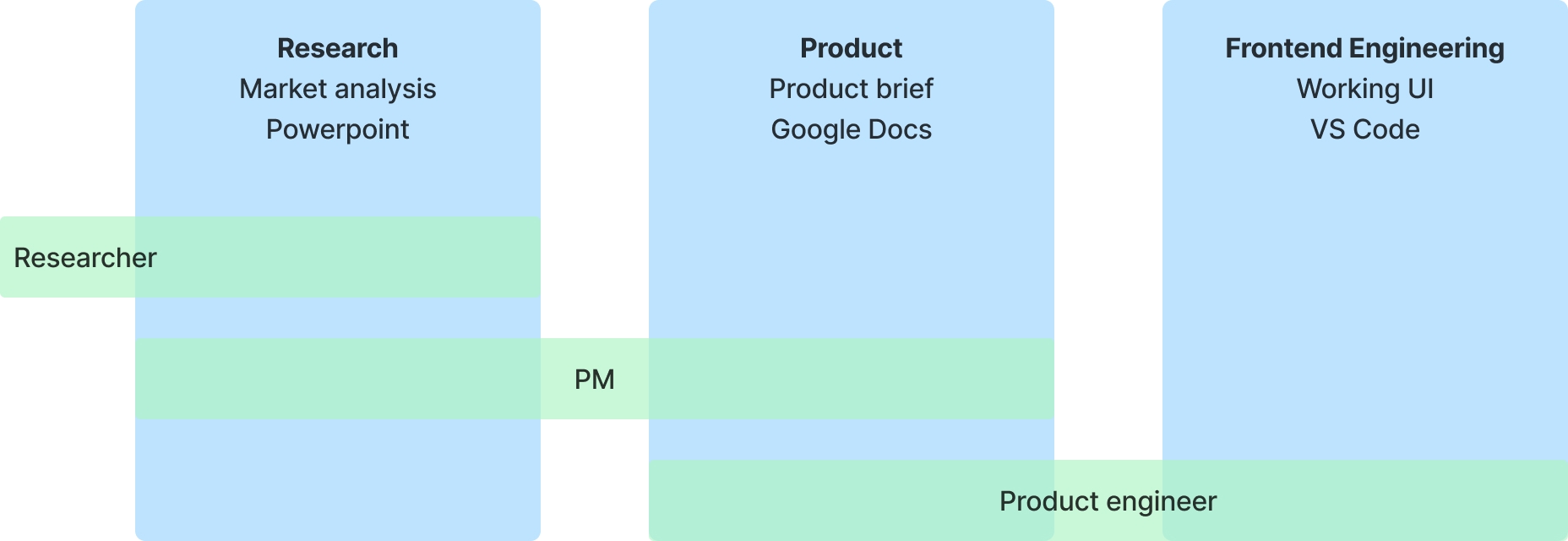

Imagine we’re starting a new product and need to do some user research, scope the product, and build a prototype of its UI. And we’re going to reorg half a seat over, aligning roles to translations, rather than artifacts:

- The PM will spend half of their effort outside of the team, directly working on user research, partnered with someone who is an expert in that area.

- The PM and product engineer will then work directly together to write a product brief. The PM can use the research that they are directly involved in, while the engineer brings their knowledge of our existing systems and technical tradeoffs. But they work together to bring all that knowledge to bear on the product brief.

- Then the product engineer can start working on the prototype, pairing with other engineers to flesh out the technical design and disseminate their deep knowledge of the product tradeoffs.

This example demonstrates how the hybrid roles have changed the way that information moves on the project:

- Solo working, within one function, has been replaced by two people pairing together on the work. Each of the people has context from a different seat, so they can work out the tension of different constraints while making decisions together, rather than having people argue at a handoff meeting.

- Handoffs have been replaced with continuity. Whenever decisions in one artifact need to impact another, we have someone who was involved with the full depth of thinking on both sides. They can apply the decision flexibly because they know the context, and they can translate the decision well into the language of each discipline, so that we don’t end up with arguments caused by misunderstanding.

This is the power of reorging half a seat to the left and aligning people to translations, rather than artifacts.

Example hybrid roles

A number of hybrid roles are already well established.

Here are some of the hybrid roles that are gaining acceptance in the world of web software. Note that some of these are roles, that an individual might take on for one project, rather than titles, that they have officially for the course of their job.

-

Product engineers are comfortable both with understanding users’ needs and with the internals of the product that can satisfy them. Paired with a PM or other user-centric expert, they can synthesize a product brief about what users need and how a product could help them. Then they can bring that rich context when making tradeoff decisions while writing the code.

-

Design engineers are a particular specialization of product engineers, focused on design prototyping for complex UIs. They are comfortable in the tools and thinking styles of both design and UI engineering, so they can come up with alternatives in Figma, participate in a design crit and explain tradeoffs, and then translate those designs into a functional UI in code. Pairing with a designer, they can collaborate on the design for a specific screen. Pairing with another engineer, they can build the UI while bringing a lot of context about the design so they can make all the right tradeoffs as they write the code.

-

System designers are designers who don’t work embedded on a specific product team, but instead focus on the entire system or language used across multiple products. When paired with a design engineer who has context on the needs of a specific product, they can collaborate to design the right behavior. They can spend the rest of their time pairing with other user-facing or design disciplines to work on the next set of reusable components or system-wide upgrades that will be needed for future work.

-

Platform engineers are a new hybrid role that has helped to bring the best of DevOps while still serving product-centric teams. While some organizations took devops to mean that teams should build and run their own systems (on whatever infrastructure they choose), most organizations have taken a more platform-centric approach, where internal teams pave pathways that product teams can use. This allows product teams to own their operations, but provides them a paved path of officially-supported tools that can help them. Platform engineering, then, is a hybrid role that works in the domain of systems engineering (building scalable platforms), but also in product engineering to make those systems usable for other teams.

For each of these roles to work, the person in it must be explicitly encouraged and given space to act in both of the disciplines they are bridging. They should be actively working together with others to make decisions. If they are just a messenger, or if they are just an expert who hands off their brilliance to others as an artifact, they are not really acting half a seat over.

How to know it’s working

When hybrid roles are working well, the work should feel different. It’s not just 10% faster or better, but instead feels more coherent, aligned, and holistic.

Here are some signals that it’s working:

- Thinking up and down the stack: when each role can identify ways their decisions could cause blocks for other disciplines, or be incompatible with some future plans, and call that out or make tradeoff decisions based on it.

- Making non-stereotypical tradeoff decisions: when context and responsibility are fully shared, roles shouldn’t be defensively giving their stereotypical answers (like a PM wanting to launch faster, or an EM wanting to sandbag estimates). It should be as likely for the PM to schedule a refactor and delay a launch, or for an EM to want to find a dirty solution to validate a hypothesis.

- Making different and interesting process mistakes each time. No team is perfect at balancing speed v quality, breadth v depth, or polish v coverage. But in poorly-run and political organizations, they make the same judgement error, in the same direction, over and over again. Progress looks like getting the balance wrong in different directions, at growing scales of complexity, over time.

The case of PMs

My first draft had several thousand words about whether or not PM is a hybrid role, whether the mythical “early Stripe had no PMs” / “Apple has no PMs” are really true, and what the future of the PM role looks like. That got so long and hotly-debated that I stripped it out and will rework it into a future post.

Elsewhere…

Things I’ve been reading this week that you might enjoy. These are almost exclusively on topics unrelated to tech, but are just good reads:

-

Return to Pachinko Road is Craig Mod’s latest pop-up newsletter. He’s spending two weeks walking along an ancient road in Japan, sharing a short daily email with beautiful photographs and poetic reflections on the people and places he runs into. Reading these daily updates, I’m inspired to spend more time walking, taking photos, and making my local neighborhood more beautiful.

-

From the Fatherland, with Love by Ryū Murakami (translated by Ralph McCarthy, Charles De Wolf, and Ginny Tapley Takemori) is a wildly comedic romp of a dystopian novel that begins with North Korea invading one of the Japanese islands and then gets weirder. Originally published in Japan in 2005, it was relevant to the cultural situation there at the time, and now feels extremely relevant to 2024 America.

-

Snackable Growth by Sabra Meretab is a lovely new newsletter by a former coworker at Stripe, who is taking a break from tech to think about other creative pursuits. The first entry was helpful and I look forward to more.

-

A New Program for Graphic Design by David Reinfurt is a condensed set of notes from a hands-on design workshop. I picked this up as fresh inspiration for a project I’m working on that I want to be nicely designed. It aligns nicely with the very personal, modernist, curation of the work and designers that this book features. The book also comes with a set of very difficult, open-ended design exploration assignments that have been fun to work on.

-

Money stuff is a several-times-a-week-ly newsletter full of dorky and funny stuff about finance. Among ex-Stripe folks, it already has a strong following, but I’m regularly reminded that most people don’t know about this, even in fintech, and they should. Monday’s edition, The Endless Shrimp Investigation, was a classic.